An Orphan Camp on Atomic Bombed Land

- Yorito Kamikuri, Father of 2,000 -

Broadcast schedule: 9:50 a.m. - 10:45 a.m. Friday, August 6, 2021

“I believed that the only way to live

was to steal like this or kill people and steal their money to survive.”

Feelings spewed by an “A-bomb orphan” after the atomic bomb robbed him of his family.

According to a survey conducted by the then Ministry of Health and Welfare in 1948, the number of orphans in Japan was approximately 120,000. Hiroshima Prefecture had the largest number at 5,975, surpassing any larger metropolitan area.

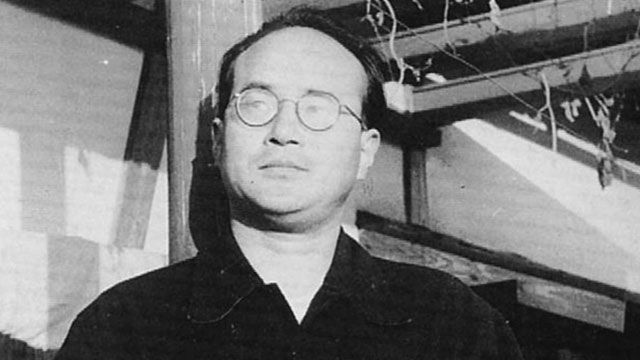

The atomic bombing 76 years ago instantly scorched the entire city of Hiroshima. Just two months later, amidst the ruins, a 26-year-old young man set up a camp for orphans with his own money. He named it Hiroshima Shinsei Gakuen, meaning Hiroshima new life school. The facility filled up with A-bomb orphans, war orphans, repatriated orphans, and many other children who had lost their families in the war.

The name of this young man who founded the facility was Yorito Kamikuri (who lived to be 76 years old). It all started with his own experience of the atomic bombing. On August 6, 1945, Kamikuri witnessed groaning people who had collapsed from exhaustion and crying babies clinging to their mothers who had taken their last breath. He would later spend his whole life regretting not being able to do anything.

Most of the orphans from those days had severed all ties with their past, keeping it a secret even from their adopted families. There was also very little documentation on them. Recently however, Haruo Shiraishi, a repatriated orphan and graduate of Hiroshima Shinsei Gakuen shared with us the story of his upbringing for the first time. During WWII while living in Taiwan, which was under Japanese rule, Shiraishi’s parents died of malaria, leaving four children behind. Shiraishi and his siblings were repatriated to the burnt-down city of Hiroshima, where they had no family or connections. As they helplessly stood at the port, Kamikuri approached them.

Immediately after the war, everyone was struggling to make it through the day. Those who somehow survived the war had to go on living, with no time to grieve. The environment at the facility was far from adequate, and hardships continued.

This program traces the unknown history of a facility that once stood on scorched land, as it conveys the wishes for peace that has brought us to the present, and sheds light on the fact that many children were at the mercy of war.

Sayuri Fukai, Director

My encounter with Hiroshima Shinsei Gakuen, currently in Higashihiroshima City, was about five years ago when I heard about a facility that was successfully rehabilitating boys and girls through group sports instruction. When I went to visit the school, I noticed many war-related objects such as a cenotaph for the victims of the atomic bombing, A-bombed rocks, and an ossuary. The facility had originally been in Motomachi, near the hypocenter, but moved to its current location.

I am a third-generation hibakusha from Naka-ku, Hiroshima City, but I had never heard of Shinsei Gakuen before. I also conducted a survey of hibakusha groups across Japan, to which most responded that they had also never heard of the name. As I continued my search, I was surprised to find that there was very little information about how orphans lived after the war. Why did Kamikuri reach out to these children at a time when it must have been hard enough just for him to survive?

Conflicts and war continue to occur even now, some say that we are facing the greatest challenges since WWII. It begs the question, are we able to hear the “small voices” calling for help, as Kamikuri did? This might be the ideal opportunity to think about it.

Through the interviews, I was reminded that in conflict, those who get hurt, those who do the hurting, and those able to reach out to help others are all human beings. I felt an urgency to tell the history of the love and hardships of one unknown citizen, who worked hard to rise from the ruins of an atomic bombed city. I felt the need to do so before the facts get buried in the past. This is why, using the few remaining references that I could find as clues, I created this program.

Profile

Third-generation hibakusha (atomic bomb survivor) born in Naka Ward, Hiroshima City. Joined Mie Television Broadcasting in 2009, and in 2011, Sayuri produced The Earthquake Through Her Eyes: A Junior High School Girl from Onagawa in Suzuka news special, winning the grand prize in the News Program Category in the TV and Visual Subcommittee Division of the Chūbu Region Photographers Association Awards. Later, she covered topics such as pollution in Yokkaichi City.

In 2015, Sayuri joined the news department at TV Shin-Hiroshima (TSS), where she was assigned to cover the prefectural police, as well as prefectural government, and worked the newsroom. She also covered the West Japan Heavy Rain Disaster. She belonged to the broadcast club in middle school and high school. Using this experience, she has served as a judge for the Hiroshima Prefecture High School Broadcast Culture Competition’s Prefectural Tournament since 2015. Her documentary, An Orphanage in the Atomic-Bombed City: Yorito Kamikuri, Father to 2,000 Children won grand prize for the Chūgoku/Shikoku Regions, as well as nationally, for Educational Programming at the 2022 Japan Commercial Broadcasters Association Awards.